Climate Change is a Class Issue

Photo by hitesh choudhary from Pexels

Ever heard of the slogan “save water, save the Earth”? Here’s the catch: saving water will not stop climate change. Well, generally, it would really help if we do it collectively, but unfortunately, these individual actions wouldn’t still be enough. Why?

Climate change has long been seen as a mere environmental issue that exists in the scope of natural sciences. “Anthropocene” is a term mainly used to emphasize humanity’s role in creating climate change. However, this term has oversimplified the notion that all humans are equally responsible for climate change. This has created the dominant framework of how we collectively see this issue and how we can resolve it together—equally.

The truth is, the idea of Anthropocene is harmful as it promotes equal responsibilities of climate change to all people. It neutralizes the burden of environmental harm felt by vulnerable groups and overlooks shareholder capitalism as the system that plays a significant role in this matter.

Historically, we have failed to see the issue of climate change in its complexity. Interdisciplinary analysis involving class, power, and politics is often missing from the narratives when it should be common knowledge at the frontline of the discourse.

Shareholder capitalism undervalues labor as a commodity and drives inequality and environmental destruction. In the case of climate change, most carbon emissions can be traced back to production for short-term profit maximization—such as fossil fuels—that is responsible for the ecological damage that ruins the lives of many indigenous people.

The history of fossil fuels itself cannot be separated from European colonialism over Africa back in the late nineteenth century. The development of oil resources in African colonies was pursued for the economic interests of the colonial powers to dominate the oil production. Experts called it climate colonialism, defined as the “deepening or expansion of foreign domination through climate initiatives that exploit poorer nations’ resources or otherwise compromise their sovereignty.”

Even after the decolonization of Africa, there are a few marks of neo-colonialism. During the oil boom in the early 2000s, American and Chinese firms tried to gain endorsement among African governments who were in control of the decision-making.

Aside from fossil fuels, southern nations have also long exported their natural resources to wealthy countries such as Germany or the United States at a lower cost than the finished products they then import for their own consumption. This has benefitted the Global North while the Global South continues to struggle with economic development and destabilization.

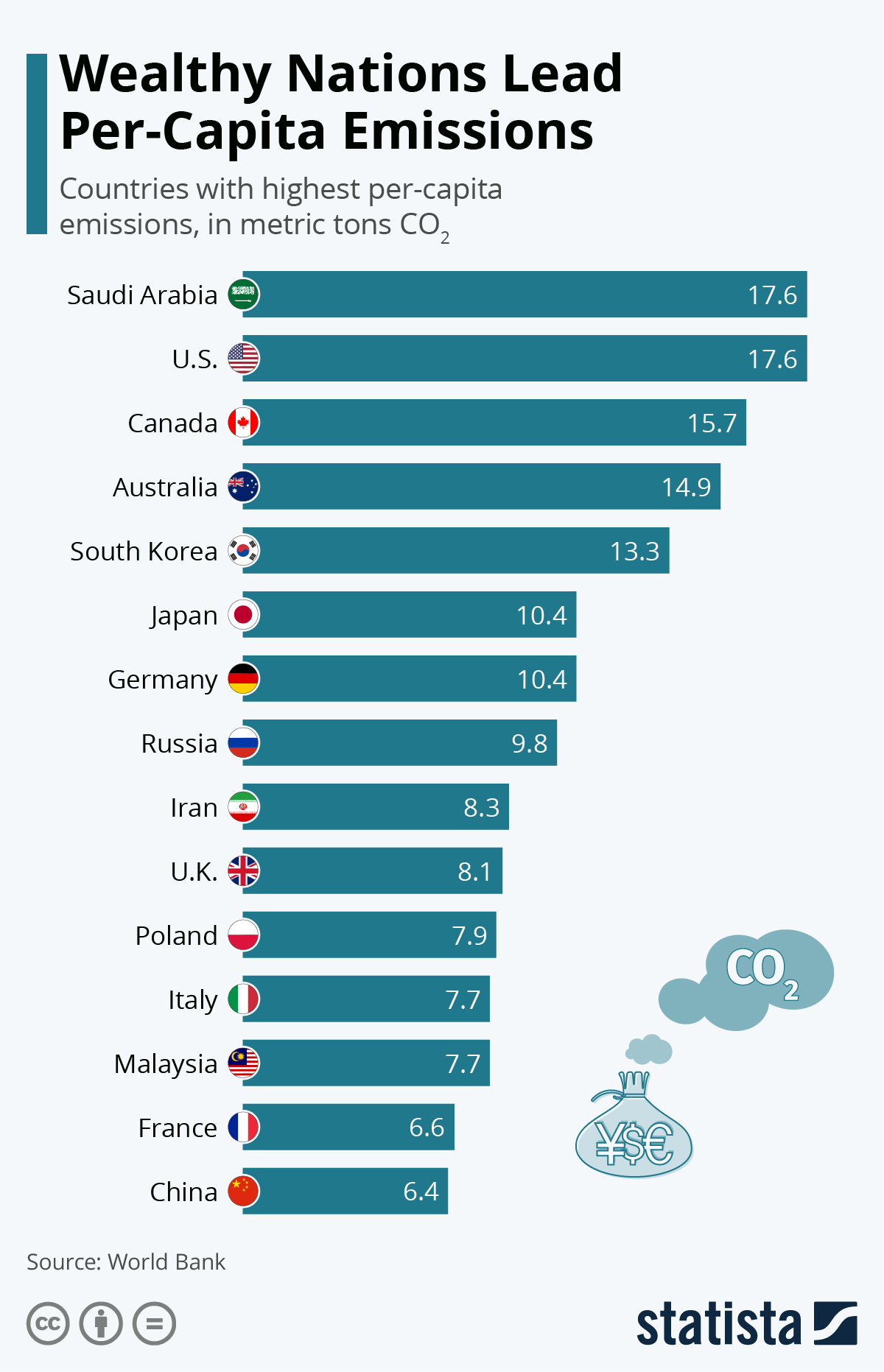

The wealthiest countries have emitted much more carbon than others. It stands to reason that they should bear a greater responsibility to cut their emissions in the effort to stop climate change.

Wealthy countries are not the only culprits. A report in 2017 revealed that there were only 100 companies who were responsible for more than 70% of the GHG emissions since 1988. Among these companies, the highest emitters were the fossil fuel producers who held the key to systemic change on carbon emissions, and still do.

Other than that, it is also revealed that the wealthiest ten percent of people are responsible for 49% of lifestyle consumption emissions. On top of that, the wealthiest people also have greater ability to rescue themselves from any climate-caused disasters by buying expensive habitable areas, leaving the poorest and most vulnerable at the forefront of climate apocalypse.

To sum up, climate change is a race of the class system, of power and economic gap between the rich and the poor. The discourse of class and climate change shouldn’t be inseparable, rather it should be intertwined and thoroughly examined. In order to prevent the climate crisis, we should collectively demand climate justice—one that addresses social, economic, political, public health, and civil rights issues of the underprivileged population. This also tells us that redistribution of resources and means of production is necessary to achieve climate justice.

It is time for us to truly wake up and advocate for a better system that yields the better livelihood of many, not just the wealthiest. The impact of climate change will not be borne equally, and our fights towards climate justice have to acknowledge the gap of responsibilities in the current system.

Climate change requires more than individual actions. Changing our light bulbs, buying organic food, and going zero-waste might be a way to fight climate change, but it will never be enough. We need a fundamental shift through decarbonization, renewable energy, carbon tax, green infrastructure, and a reformed global policy that pursues climate justice in the long run.

Editor: Nazalea Kusuma

Adelia Dinda Sani

Adelia is a Contributing Author at Green Network Asia. She studied Communications & Media undergraduate program at Universitas Indonesia, as well as English Literature at SWPS University of Social Sciences and Humanities in Warsaw, Poland.

Test premium post

Test premium post  Electric Vehicles Roam the Roads of Kenya

Electric Vehicles Roam the Roads of Kenya  Come Back Stronger: Building Philippines’ Resilient Economy Post-COVID-19

Come Back Stronger: Building Philippines’ Resilient Economy Post-COVID-19  Inside Experian’s Sustainability Journey: An Interview with Chief Sustainability Officer Abigail Lovell

Inside Experian’s Sustainability Journey: An Interview with Chief Sustainability Officer Abigail Lovell  How Protection Law and Global Commitments Can Accelerate China’s Wetland Conservation

How Protection Law and Global Commitments Can Accelerate China’s Wetland Conservation  How Biotechnology Can Support Food Security and Energy Transition

How Biotechnology Can Support Food Security and Energy Transition  Test Custom Feature Image

Test Custom Feature Image