Public Health Expert Professor Tikki Pangestu: Vaccination Coverage is Key to Managing the COVID-19 Pandemic

Professor Tikki Pangestu at Lee Kwan Yew School of Public Policy SIngapore | Photo: Channel News Asia

Indonesia has been widely reported as the new epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in Asia since the past month. As of August 4, 2021, the total reported deaths had surpassed 100,000 souls, making Indonesia the second country in Asia after India to achieve this grim “milestone”. Public health experts believe that due to limited testing and tracking, the actual death toll of COVID-19 patients in Indonesia is higher than recorded.

Recognizing this ongoing health crisis, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy Alumni – Indonesia Chapter invited Professor Tikki Pangestu to give a keynote speech entitled “Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic for Public Policy Practitioners” in an online alumni gathering, followed by a Q&A session.

Professor Tikki Pangestu is a public health expert of international caliber. Prof Tikki, as students and alumni usually call him, is a visiting professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy and the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore. Prior to joining the two institutions, he worked as Director of Policy Research and Cooperation at the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva, Switzerland, for 13 years.

This publication documents his keynote speech, including the Q&A session with the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy Alumni – Indonesia Chapter in a 30-minute Zoom session on Saturday, July 17, 2021, 04.00 PM – 04.30 PM Jakarta time.

What are the latest key facts from around the world regarding the COVID-19 pandemic?

In short, there are some facts related to the COVID-19 pandemic that we can see today. As reported to WHO, there have been more than 190 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 worldwide, with over 4 million deaths.

Western Europe and the United States have begun to open up. Asia is “burning”, and I fear Africa is like a ticking time bomb. We hope that there will be no disasters (COVID-19 health crisis) in Africa.

Today, we are also very worried about the Delta variant which is highly transmissible and more infectious, and has spread to more than 100 countries globally.

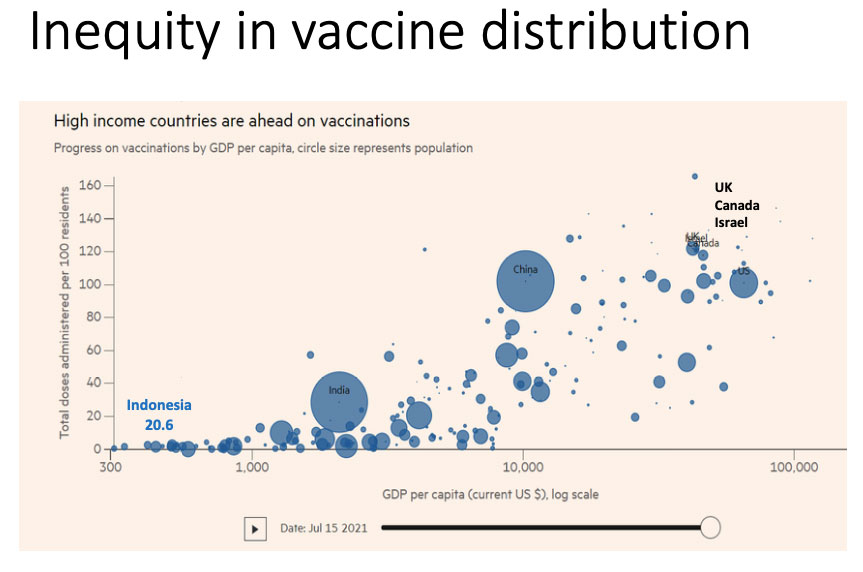

One of the most important updates is that vaccination coverage remains very limited and unequal, especially in developing and low-income countries.

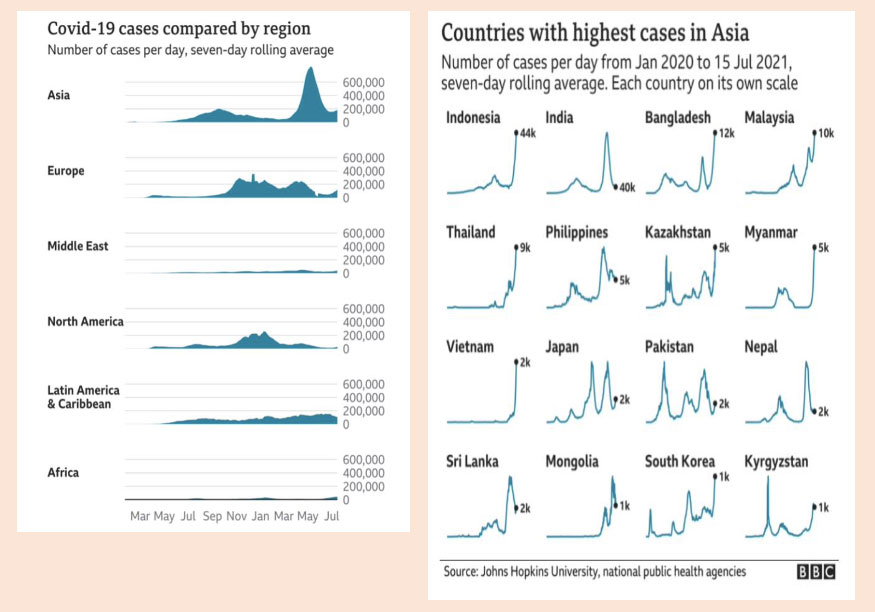

As we can see, Asia is starting to become the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic. The figure is very high compared to other regions. We can see that infection cases in Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Myanmar, and South Korea have continued to rise in the last two weeks.

Which countries have managed the COVID-19 pandemic well?

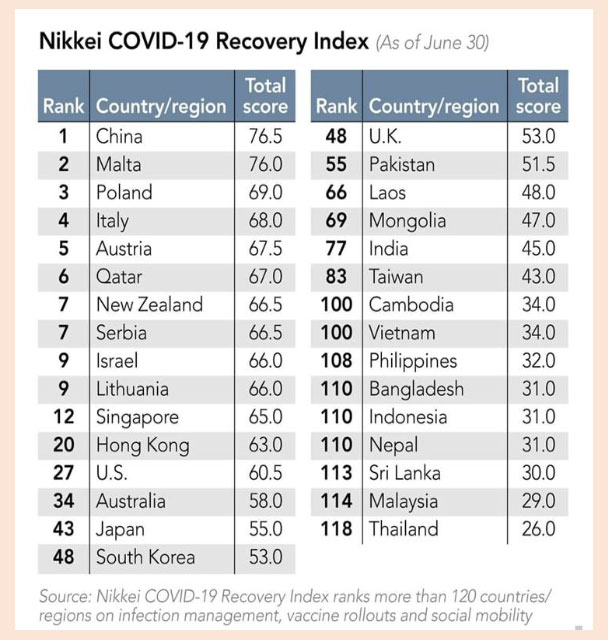

Many people say Singapore is one of the countries that has managed the pandemic well. In my opinion, the country that has managed the pandemic best is China. It can be seen from the Nikkei COVID-19 Recovery Index, where China ranks first, and this is related to many factors. We can also see that New Zealand has been quite successful.

Are there good practices other countries could learn from them? What lessons have been learnt for public policy from the COVID-19 pandemic to date?

First, speed of reaction. Countries that can manage the COVID-19 pandemic well have responded to this pandemic quickly.

Second, a robust healthcare system, which effectively uses information technology interventions for testing, contact tracing, detection and treatment of positive cases in hospitals, for treating patients who require oxygen or ventilators in the ICU, and isolation.

Third, good governance. This includes good political will and strong leadership, including unity of purpose, common goals, and coordination. No confusion, no duplication.

In Singapore, for example, there is the Multi-Ministry Taskforce, a special cross-ministerial team for the COVID-19 response.

Fourth, which is no less important, is social capital. Citizens and members of society who obey the rules.

This is about social awareness that our course of action is not only to protect ourselves, but also to protect the greater good in the community, especially on public health. Indeed, this is also related to the people’s trust in the government.

Fifth, vaccination. This is strongly linked to the social capital I mentioned earlier. If you don’t believe that vaccination is important, look at the difference in cases between the UK and Indonesia.

As of 16 July 2021, there were 48,359 cases with 63 deaths in the UK, and 54,000 cases with 982 deaths in Indonesia. What distinguishes the two? Undoubtedly the vaccination coverage! Vaccination coverage in the UK has reached 68%, while in Indonesia only 15%.

This is just one source of data. There is a wealth of data showing that vaccinations reduce mortality. In other cases, it reduces the severity of patients admitted to the ICU, or those who may need a ventilator and have a high risk of fatality.

What is the current status of COVID-19 vaccinations?

Vaccine supplies are not equally distributed around the world. Most vaccines are available in high-income countries such as the UK, Canada and Israel. Very few doses of the vaccines have been given in low-income countries.

Indonesia has only vaccinated about 20.6 per 100,000 population. There is inequality in the distribution of vaccines across countries.

What are the barriers to vaccine implementation in Indonesia? How to increase vaccination coverage?

First, insufficient supply. We know that’s definitely insufficient. This is related to the fact I mentioned earlier that most vaccines are still available only in rich countries. Developing countries have not yet received the required share.

Second, logistic barriers. We can give vaccines in Jakarta, Yogyakarta and Surabaya, but what about in Papua, Maluku, Sulawesi, etc.?

The problem of logistic barriers is very crucial for a country like Indonesia. There are challenges such as vaccines that must be stored at the right temperature, insufficient facilities and health personnels to administer vaccines correctly and safely.

Third, vaccine hesitancy. This is related to the social awareness I mentioned earlier. In Indonesia, a relatively high number of the population have not accepted the fact that vaccines are important not only for themselves, but also for the community.

There is research showing that Indonesia witnessed one of the largest falls in public trusts worldwide between 2015-2019. There has been a decline in public trust towards the government regarding perception of safety and effectiveness of vaccines.

This is caused by various factors. For example, the perception that vaccines contain substances that are non halal. It is important to understand that it means many people still do not want to receive vaccines. This is a public policy challenge.

We also know that vaccine hesitancy is also linked to disinformation. Hoaxes, conspiracy theories, and propaganda have been facilitated by social media. We know a lot of disinformation is spread on Facebook, Twitter, etc. This is a public policy challenge as well.

Addressing inequality in vaccine distribution across countries, what are the governance solutions from multilateral organizations and countries, so that we can tackle this health crisis together, given that “no one is safe until everyone is safe”?

In short, governance at the global level is important, but governance at the national level is also very important. At the global level there is COVAX, a multilateral initiative whose sole aim is to increase developing countries’ access to vaccines.

The initiative is funded by the World Bank, IMF, and coordinated by WHO, Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), Gavi, and UNICEF. So it’s really a multilateral global initiative. That’s the main hope at the global level.

At the national level, in this situation we should not always be dependent on external support.

For Indonesia in particular, this is also public policy; we need to consider domestic vaccine production. This is something that has been mentioned by many experts, that in the future Indonesia must be self-sufficient.

Indonesia has a pretty good capacity, for example in Biofarma. The government needs to prioritize local pharmaceutical industries with the expertise and facilities to produce vaccines.

Maybe some of you who work at the Ministry of Industry or the Ministry of Health can help promote that Indonesia must be self-sufficient in the future.

If Indonesia has a sufficient and strong domestic vaccine industry, it will not only be beneficial domestically, but the country can also generate income from export to the ASEAN region, for example.

If Indonesia can export vaccines, not only COVID-19 vaccines but vaccines for other diseases as well, it will be a source of income for the government.

There is a trade off between economic growth and the health crisis. How does the government find an equilibrium point from the perspective of public policy?

This will vary from country to country. In China, for example, the government can act decisively because their economy is quite resilient, and that is very different from the situation in Indonesia.

Balance will only be achieved if we get to a point where our healthcare system is not too overwhelmed. It is very difficult to reach that point before the vaccination reaches a certain point of coverage. So the priority right now is for healthcare before the economy resumes.

Unlike in China, we know that the lockdown in Indonesia is a micro – not a total – lockdown, because many citizens work every day; if they don’t work they don’t eat.

In my opinion, if vaccination coverage starts to increase, it can be adjusted more fairly. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic impact the poor, those with low incomes, most severely.

The problem of rule disobedience is indeed challenging from the public policy perspective. The most important thing in my opinion is the right communication strategy, which can reach those we can influence to improve their discipline.

The response must involve various ambassadors to spread information about the pandemic and vaccines, including but not limited to the Ministry of Health, professors from universities who have authority, community leaders, and religious leaders, who can exert influence.

In the area where I live in Jakarta, the RT and RW (neighborhood) heads can play a very effective role. The response could also involve celebrities, movie stars, singers, athletes, anyone who can influence the public

In fact, many citizens don’t really relate when, for example, see the minister of health getting vaccinated. However, they relate and believe in “people who have the same face as me and speak like me.”

Campaigns can be delivered in local languages such as Javanese, Sundanese, etc., so that people can relate to the cause. That is a reality all over the world.

There is a survey in Indonesia showing that celebrities have a strong influence for vaccination purposes. When they do the campaign, the effect is stronger when they speak with their own words and styles, not as the literal message as the health minister speaks.

The point is to advocate with the right communication strategy, using the right messenger.

How do you see our situation in the future?

In my opinion, in the future, in the new normal, COVID-19 will be like a kind of new flu. From a public policy perspective, strategies that are readily available in place are needed.

It is necessary to increase vaccination coverage while maintaining stringent health protocols, since vaccination is not a magic bullet! There should always be surveillance and monitoring in case there is an outbreak. This could happen, a new variant of COVID-19 might emerge. We also need better social responsibility.

With various challenges to transition towards a new normal, all responses require public policies. Today, effective public policies are important and more crucial now, more than ever.

We need to keep in mind that developing public policy is not easy. Sometimes it can cause controversy. I would like to quote Albert Einstein that, “What is right is not always popular, and what is popular is not always right”.

In the future, those of you who will be the ones who determine public policy must have the courage to make right and effective policy decisions.

-Finished-

Editor: Agung Taufiqurrakhman

Marlis Afridah

Marlis is the Founder & CEO of Green Network Asia. She holds a master's degree in Public Policy from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore. She is an interdisciplinary public policy researcher and public affairs practitioner with an integrated focus on sustainability and sustainable development. She brings over a decade of cross-sector professional experience supporting governments, businesses, and civil society across the Asia Pacific and beyond, mainly on policy research and advocacy, government relations, and stakeholder engagement.

Electric Vehicles Roam the Roads of Kenya

Electric Vehicles Roam the Roads of Kenya  Come Back Stronger: Building Philippines’ Resilient Economy Post-COVID-19

Come Back Stronger: Building Philippines’ Resilient Economy Post-COVID-19  Inside Experian’s Sustainability Journey: An Interview with Chief Sustainability Officer Abigail Lovell

Inside Experian’s Sustainability Journey: An Interview with Chief Sustainability Officer Abigail Lovell  How Protection Law and Global Commitments Can Accelerate China’s Wetland Conservation

How Protection Law and Global Commitments Can Accelerate China’s Wetland Conservation  How Biotechnology Can Support Food Security and Energy Transition

How Biotechnology Can Support Food Security and Energy Transition  Thinking Through Product Life Cycle and Good Practices for Sustainability: An Interview with David Croft from Reckitt

Thinking Through Product Life Cycle and Good Practices for Sustainability: An Interview with David Croft from Reckitt  Test Custom Feature Image

Test Custom Feature Image  Test premium post

Test premium post