How Veterinarian Sugeng Dwi Hastono Takes Care of Sumatran Wildlife and How We Can Help

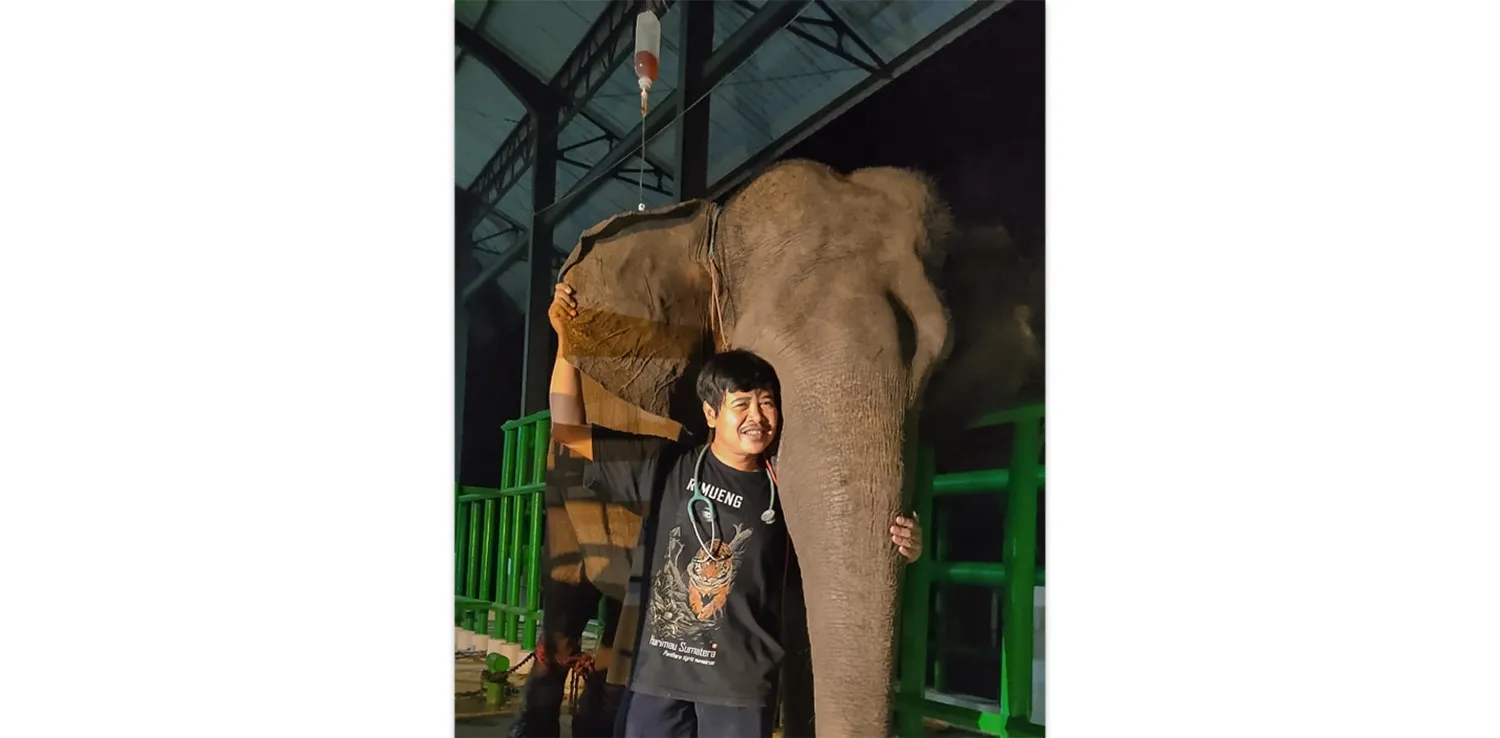

Dr. Sugeng with his team after a discussion about wildlife conservation.

Animals are a critical part of our biodiversity. In pursuing a better future, our biodiversity must not be left behind. Animal welfare is a big part of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 15 is to protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss. Though we all need to do our part, veterinarians are no doubt a key element.

On Saturday (8/28), Green Network interviewed veterinarian Sugeng Dwi Hastono via Zoom. Familiarly called Dr. Sugeng, he is a veterinarian based in Natar, Lampung, Indonesia. He earned his Doctor of Veterinary Medicine from the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine Universitas Gadjah Mada in 2002. Since then, Dr. Sugeng has been active in the field.

Dr. Sugeng opened his private practice in 2009, intending to work with all species, including pets, wildlife, exotic animals, and others. He took, and still takes, the necessary training and additional workshops to round out his knowledge in all species of animals. Dr. Sugeng named his private practice Amanah Veterinary Service in 2011.

Besides his private practice, Dr. Sugeng is also a part of the Assessment Institute for Foods, Drugs, and Cosmetics Majelis Ulama Indonesia (LPPOM MUI) Lampung. He often gets called to share his knowledge and insight through training, seminars, workshops, and talks. As of this semester, he is also an adjunct lecturer at Universitas Gadjah Mada.

Today, we would like to highlight Dr. Sugeng’s contribution and insight on human-wildlife conflict management and wildlife conservation. He has over a decade of experience in taking care of wildlife across Sumatra, Indonesia.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) defines human and wildlife conflict as any human and wildlife interaction which results in negative effects on human social, economic, or cultural life, on wildlife conservation, or on the environment. Dr. Sugeng shared that as per Indonesia’s Ministerial Regulations No. 48 and 53 from 2008, a veterinarian leads all operations in human-wildlife conflicts.

What constitutes a human-wildlife conflict? Please share with us the general overview.

A human-wildlife conflict must consist of humans, wildlife, and their environment or habitats. It might result in wildlife, human, or property casualties. For instance, wildlife going into a human’s living area or settlement. That populated area could be an actual land intended for humans or a part of the forest that has had a functional shift.

For example, an elephant caught in a trap is not a human-wildlife conflict but a victim of hunting activities. A human-wildlife conflict would be when an old elephant – because elephants live long – goes back to an area that used to be their playground or full of food sources, but today, it is a village full of humans, houses, and farms.

Generally, the main goal of human-wildlife conflict management is to save humans without sacrificing wildlife. Personally, as I am a veterinarian, my priority is the wildlife.

How do you know where and when to go?

I receive calls from National Parks, conservation centers, Non-Governmental Organizations, and even the Ministry of Environment and Forestry of The Republic of Indonesia when the case is very important. Of course, there’s bureaucracy, too. To enter National Parks, we need a permit called SIMAKSI.

Sometimes it’s for medical emergencies, general check-ups, translocations, or educating the locals; other times, it’s to lead an operational team for conflict management.

Can you tell us a story of one of the most memorable operations you have completed?

In 2015, there was a Sumatran tiger sighting behind a bank in Wonosobo, Tanggamus. The villagers thought it was siluman, a person supernaturally masquerading as a tiger to steal money. I first received a call at 10 AM, but I had another obligation all day. I finally left at 5 PM and arrived at the location at 8 PM. After eating, planning, and active movement, the tiger was evacuated safely after midnight at 1 AM.

The tiger had gone into people’s houses. It entered someone’s kitchen by breaking windows. This conflict happened in a highly-populated area. There was also added chaos because people from that village and nearby villages were curious and came to watch. This was a full-blown operation involving the military and police force.

From your extensive experience, what problems have you noted that can be improved for better wildlife welfare?

It is the connection from the remote government to the central government. I am not saying they are bad at communicating. The problem is more on the technical side. Communication technology-wise, it is hard to relay reliable information in time from remote locations because there is no cell signal, let alone the internet. Transport to reach those areas is also challenging because the roads are bad with complicated routes and limited vehicle options.

Those things are crucial for time-sensitive situations and still important for less urgent situations. When I went to South Bukit Barisan National Park to educate the locals, I experienced those things, making things harder. Improvement in communication technology and transport is recommended.

Is there anything else?

I think the lack of veterinarians who specialize in wildlife also makes things more difficult. I have seen conservation centers with so many animals but only one veterinarian in charge.

How can we solve that problem?

One solution is to give general and basic training on wildlife to local veterinarians in select locations where wildlife problems likely occur. This is done to utilize existing human resources; so they can help properly and hold the ground until wildlife experts can come. For example, I gave training for veterinarians in Bengkulu/Palembang area on how to treat wildlife back in January 2020 before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Networking is also essential to enable knowledge sharing. I am a part of Asliqewan, an association of Indonesian veterinarians for wildlife, aquatic, and exotic animals. I think everyone in veterinary medicine should be able to ask around when specific expertise is needed. Recently, I received a call asking for assistance in the technical knowledge for the posthumous treatment of dead Sumatran tigers in the northern part of Sumatra, including how to do an autopsy properly.

Would you please share your insight on wildlife conservation? Why is it important? What is the principle?

For me, the bottom line of wildlife conservation is that wildlife belongs in the forests and humans belong in cities and villages, and nobody should cross that line. “Crossing that line” could be building houses and villages on forest land, hunting wildlife for their body parts, and taking wildlife as pets.

There is a risk of zoonosis in taking wildlife as pets. Zoonosis is an infectious disease from a non-human animal that gets passed on to humans. For example, when people buy monkeys or other primates to be their pets, many diseases can be passed on to humans.

Even if the belief is that forests exist only to fulfill human needs, we must remember that those needs do include not only resources and entertainment but also education and conservation. It is in our best interest to conserve wildlife and its habitat so we as humans can know and see their existence and learn from them. I have never even seen Javan tigers that went extinct in 1980, let alone Bali tigers that went extinct in 1925, and that’s too bad.

It is especially imperative in Sumatra. Sumatra has endemic wildlife such as Sumatran tigers, Sumatran elephants, Sumatran rhinos, and others, so we really must do our best. What if our grandchildren will not know of Sumatran tigers? What if Sumatran tigers no longer exist in Sumatra, so we have to ask institutions from other countries to see a Sumatran tiger?

What recommendations can you give the government to improve their effort in wildlife conservation and human-wildlife conflict management?

As I have mentioned before, fixing the communication technology and transport problem is critical. Another recommendation would be better regulation and stricter enforcement of land use laws, especially around forests and national parks.

What about regular people? How can we help?

Report! It is so easy yet so effective. If you see any postings on social media about selling or looking for wildlife ‘pets’, please immediately report them to local authorities. That is easy to do these days because local police departments and rescue organizations have Instagram accounts and other direct lines, so you can simply do your part from your room. This is a simple but crucial step because the authority cannot see everything all at once.

Additionally, being mindful and reducing our use of plastic and wood is good. Reducing plastic use is important because plastics can be brought to wildlife habitats and threaten their lives with their shapes and longevity. When using woods, please keep in mind that it is better to trace back its origins and make sure it is not woods planted in protected areas.

Do you have other general recommendations to mitigate and minimize human-wildlife conflicts and improve wildlife conservation?

Preventing forest encroachment is the first thing that comes to mind for the obvious reason that forests are their habitats.

Educating people is essential. First, educating locals on how to mitigate the conflict—sharing the knowledge on, for example, what to do when they see a tiger on the street and avoid shooting or poisoning them. Second, educating children. Children are our future. Teaching the importance of animal welfare should start early. It is often harder to educate and convince the adults who are already active participants in hunting or illegal trafficking, but children are our hope. Third, educating city people, too. Often, they are the market. They are the ones who ask for ‘pets’ from the forests. When hunters lay traps, endangered animals could be the ones getting trapped instead.

Another thing is an emphasis on stopping hunting activities. This includes hunting for illegal trafficking and hunting to get rid of pests. For example, villagers killing off boars because they are pests for their farms is a dangerous practice. Boars are important to the ecosystem because boars are food for bigger, carnivorous animals. When they do not have enough food sources, they will come out of the forests to look for food, leading to human-wildlife conflict.

Thank you so much for your insight and stories. Do you have any closing messages?

There needs to be synergy from all sectors in wildlife conservation. We need a collective awareness to take care of our Earth. We cannot look at things from just one way or for a short term. When making decisions, we must consider all angles.

For instance, to limit fossil fuel use, people turn to geothermal. What happens when the geothermal source is in the middle of a forest? We need to consider factors like how the forest is a habitat for wildlife and home for other biodiversity elements and how the roads that need to be built to reach the location take up land.

Another example is how forests in Kalimantan turn into palm tree plantations, citing community prosperity. Which community does it empower? What happens to our oxygen supply? What about the wildlife? Are we looking into the future?

From an Islamic perspective, it is said that God created nature so humans can benefit from it. That is true. Still, we must remember that taking benefits from nature does not mean exploiting and destroying it.

Editor: Marlis Afridah

If you find this article insightful, subscribe to our Weekly Newsletter to stay up-to-date with sustainable development news and stories from multistakeholder communities in the Asia Pacific and beyond.

Nazalea Kusuma

Naz is the Manager of International Digital Publications at Green Network Asia. She is an experienced and passionate writer, editor, proofreader, translator, and creative designer with over a decade of portfolio. Her history of living in multiple areas across Southeast Asia and studying Urban and Regional Planning exposed her to diverse peoples and cultures, enriching her perspectives and sharpening her intersectionality mindset in her storytelling and advocacy on sustainability-related issues and sustainable development.

Inside Experian’s Sustainability Journey: An Interview with Chief Sustainability Officer Abigail Lovell

Inside Experian’s Sustainability Journey: An Interview with Chief Sustainability Officer Abigail Lovell  Thinking Through Product Life Cycle and Good Practices for Sustainability: An Interview with David Croft from Reckitt

Thinking Through Product Life Cycle and Good Practices for Sustainability: An Interview with David Croft from Reckitt  AC Ventures: ESG and Impact Investing in Southeast Asian Startups

AC Ventures: ESG and Impact Investing in Southeast Asian Startups  Jendela Papua: Reflection of Us, Papua, and Indonesia, for the World

Jendela Papua: Reflection of Us, Papua, and Indonesia, for the World  Exploring the Role of Food and Women in Sustainability Education for All with Sustainability Scool

Exploring the Role of Food and Women in Sustainability Education for All with Sustainability Scool  Sakola Wanno in Conserving the Nature and Culture of Sumba Island

Sakola Wanno in Conserving the Nature and Culture of Sumba Island  Test premium post

Test premium post  Electric Vehicles Roam the Roads of Kenya

Electric Vehicles Roam the Roads of Kenya  FedEx Engages Employees with Beach Clean-Up Initiative

FedEx Engages Employees with Beach Clean-Up Initiative